THE WYETH / TARZAN REPORT — Part 3

©2014 Philip NormandThe Actual Painting of THE RETURN OF TARZAN

WHEN THE JUNE, 1913, issue of New Story Magazine with the first installment of THE RETURN OF TARZAN appeared (Tarzan dressed in a European riding outfit accompanied by an Arab rider), Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote to the editor, Archie Sessions, and asked if the cover art was for sale. According to the story as reported in Irwin Porges’ Edgar Rice Burroughs, The Man Who Created Tarzan (Brigham Young University Press, 1975), Ed had also written to the editor of All-Story magazine, Thomas Newell Metcalf, about the cover art by Clinton Petee used on the October, 1912, magazine publication of TARZAN OF THE APES. The answer came back from Sessions that Wyeth’s price for the New Story cover was $100, four times what Burroughs could afford. Ed responded to Sessions, “… I am afraid that Mr. Wyeth wants it worse than I do, so I shall be generous and let him keep it.” Unable to buy that piece he wrote back to Metcalf explaining that he had hoped to acquire the two paintings as “companion pictures” but since he could not get the Wyeth he had decided to not get the Petee either. This even though Metcalf had offered to sell the Petee for $25, “entre nous” !

Interestingly, the exchange with Sessions indicates that though Street & Smith had paid for the painting, and kept it in their holdings as we shall see, their contract with Wyeth must have stated that any secondary sale of the art was to accrue to the artist. Otherwise why would Sessions involve N.C. in the potential sale?

Fast forward 52 years to October, 1965, where an article on N. C. Wyeth by illustrator Henry Pitz is published in American Heritage magazine accompanied by a showing of 20 of Wyeth’s works. At the top of a small gallery of black and white thumbnails of various cover designs is the art for RETURN with a mention in the sidebar caption that “He did an early Tarzan, … .” A picture credit for the piece indicated that the cut was from the Graham Gallery in New York. Reverend Henry Hardy Heins, compiler of A Golden Anniversary Bibliography of Edgar Rice Burroughs (Donald M. Grant, 1964), saw the article and brought it to the attention of Hulbert Burroughs, eldest son of ERB and vice-president of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

Graham Gallery, established in 1857, was handling a large collection of cover art which had been acquired by Conde Nast Publications when they bought all of Street & Smith's holdings in 1957-59. Hulbert Burroughs negotiated for the purchase of the painting in November, 1965, paying $1,500 for it, and it now hangs in the offices of ERB, Inc. Some Wyeth art had come to Burroughs at last.

But what had befallen the art during the time that Street & Smith had it in their vault or on their office walls? A close look at the piece shows some startling differences between any of the early reproductions and the original art, but few who looked at it in the ERB, Inc. offices seemed to see them. A mention of the sale had been printed in The Gridley Wave, the small newsletter of The Burroughs Bibliophiles in December, 1965, but no photo appeared with it. Nine months later, in September, 1966, Hulbert Burroughs was the guest of honor at the Burroughs Bibliophiles Dum-Dum, a luncheon and group of panels held in conjunction with the 24th World Science Fiction Convention (Tricon) in Cleveland, Ohio. Hulbert showed slides of some of ERB's artwork, cartoons and sketches, along with photos of the Tarzana office and collection. Among the pictures was the first public showing of the recently acquired N.C. Wyeth. Though the shot of the painting elicited a number of covetous comments, no one recognized that anything might have been odd about it. Soon after the sale Rev. Heins asked Hulbert to take a photo of the painting along with the New Story cover and the first-edition book in jacket. That photo clearly shows that the painting looked exactly as it does today. Again, neither Hulbert Burroughs nor Rev. Heins noticed anything. Apparently all doubts about the difference between the painting and the printings was always put down to some inadequacy in early reproduction processes and left at that. No one thought to question whether the face in the painting might not be worthy of the accomplishments of a master illustrator.

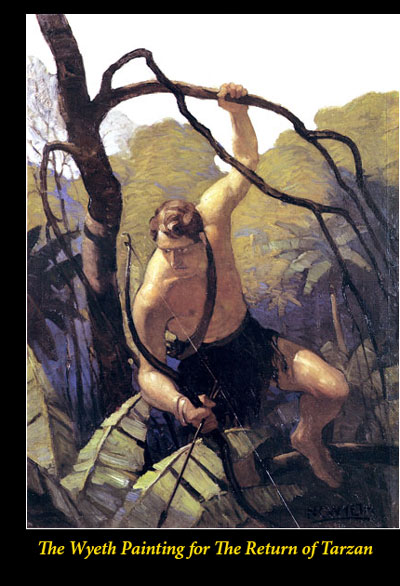

A photo of the painting as it hangs in the ERB, Inc. offices was first published in Russ Cochran's 3-volume set, The Edgar Rice Burroughs Library of Illustration (Russ Cochran, 1976), volume 1. It was reprinted more recently, in 1997's Pulp Art by Robert Lesser (Gramercy Books/Random House). The detail below is taken from that reproduction.

Roll your cursor over the image to see the differences.

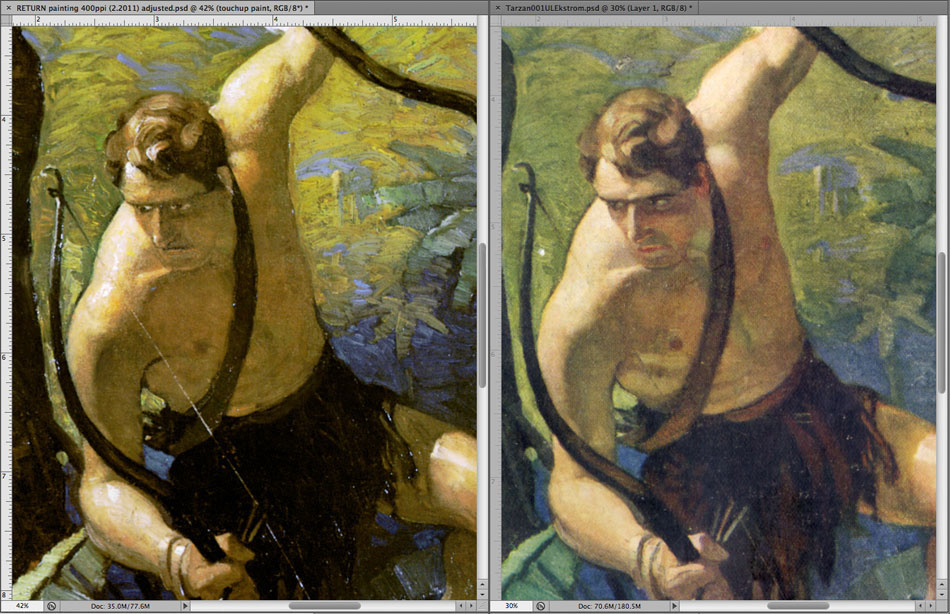

On the left is a detail from the N.C. Wyeth painting. On the right is the same portion of the art on the New Story cover.

Looking at the rollover image it is plain that the dark line below Tarzan’s nose, which is supposed to represent his upper lip in the painting, has been misplaced and what appears as his lower lip is actually the correct position, as shown in the magazine cover, for his upper lip. Thus the entire mouth has been placed too high and too close to the nose. The line demarcating the underside of the nose has also been changed.

The other most obvious change is the position and detail of Tarzan’s eyes and the shape of his ear.

Other details worth noting are the absence of underlighting on the figure’s right chest and the quiver strap and the line of demarcation of the underside of the right shoulder which is more consistent with the A.C. McClurg and A.L. Burt reproductions. Completely missing is the small highlight on the forehead directly over the nose, a detail that shows the same in all reproductions.The loss of definition in the loin cloth, belt and arrows may be an issue with the exposure of the photograph and would have to be compared directly to the actual painting for any confirmation.

The modification of the face alone establishes that the painting has been retouched. There is nothing there that could possibly have been painted by N.C. Wyeth given his masterful skills at that point in his career. The face and upper torso exhibit all the signs of having been retouched by someone not an accomplished illustrator. In fact, the face as it looks now resembles very closely the reproduction on an out-of-register A.L. Burt or Grosset & Dunlap reprint.

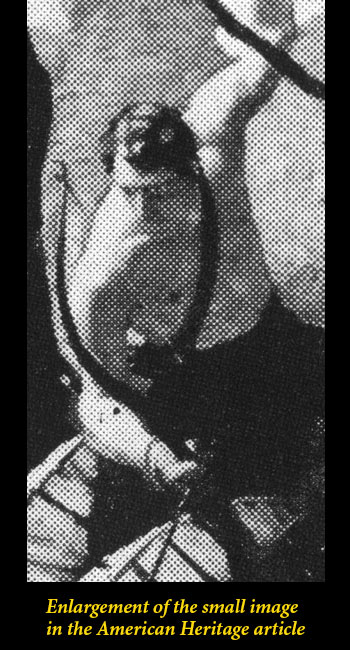

There’s no other photo of the painting before Graham Gallery supplied the small cut for American Heritage. Was that photo much larger and more detailed? Perhaps Graham has the original of that photo in their files. It appears, from this enlargement of the American Heritage cut that the painting was given to them in its present state, but why did they not notice the discrepency between the quality of painting in other Wyeths they had handled and this one?

One speculation about the modification of the painting concerns the fact that it had been at Street & Smith for all those years. It had not been given away to an advertiser or taken home by an editor for his own use as was often the custom. Quentin Reynold’s The Fiction Factory (Random House, 1955), gives us a look at the Street & Smith Art Department where William “Pop” Hines ruled the roost as Art Director. Amos Sewell, later a well-known cover artist for The Saturday Evening Post, mentions that “Pop Hines always kept a wet palette in his office. We'd bring in our illustrations, and if he didn't like them he'd tell us to get busy and change them then and there.” Did something happen to the painting and someone used Pop Hines’ palette to fix it up?

Another speculation is that the painting was damaged when it was in Chicago getting re-photographed for the A.C. McClurg & Co. dust-jacket. Might it have been retouched there? We'll probably never know the exact answer.

Continue to part 4: Conclusions >