THE WYETH / TARZAN REPORT — Part 1

©2014 Philip NormandN.C. WYETH and NEW STORY MAGAZINE

NEWELL CONVERS (N.C.) WYETH was one of America’s most popular illustrators during the Golden Age of Illustration. A star pupil of Howard Pyle’s School of Art, he began to sell to magazines at the age of 20 in 1903 and contined creating magazine illustrations for most of his career. Perhaps his most famous book work came from the commissions from Scribners Publishing for their Illustrated Classics series of great adventure novels beginning in 1911 when his unforgettable paintings for TREASURE ISLAND were published.

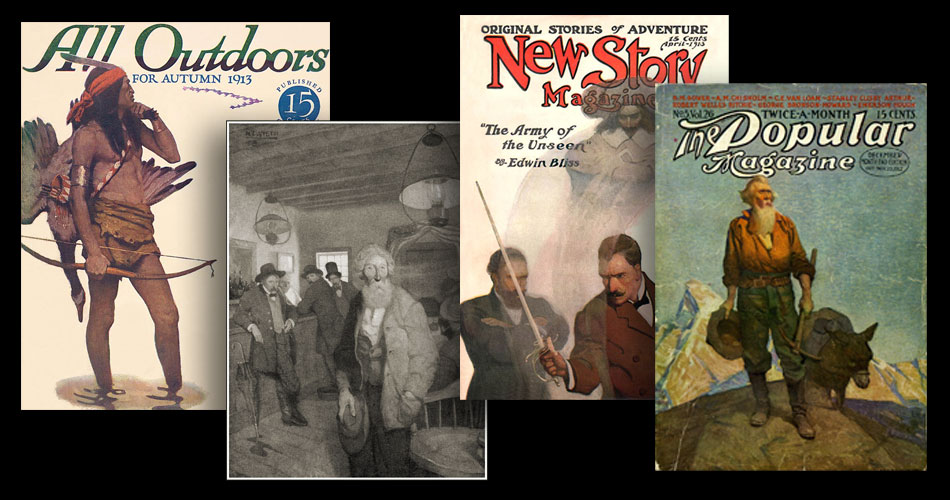

New Story Magazine was started in Chicago, in 1905, under the name Gunter's Magazine. It went through several name changes from 1910 until August of 1911 when it was retitled New Story Magazine and then sold in February 1912 to Street & Smith Publications, the premier publisher of pulps in New York. Wyeth's work for New Story Magazine began in October of 1912 while he was also providing covers and interior art for over eight different magazines.

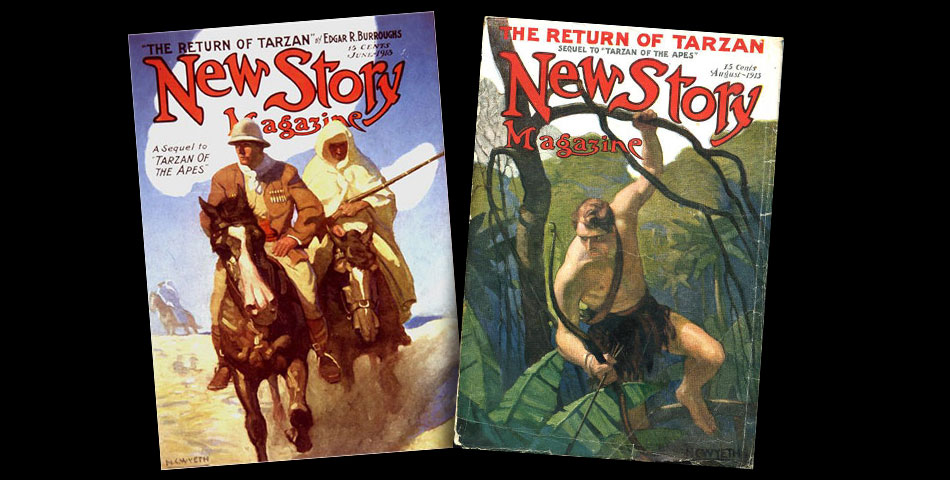

In the spring of 1913 he was commissioned to create two covers for the publication of parts 1 and 3 of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ second Tarzan story, THE RETURN OF TARZAN. The first, published on the June issue, portrayed Tarzan dressed as a European on a mission for the French Ministry of War in North Africa. The second, on the August issue, showed Tarzan as we think of him most often, clad only in a loincloth, carrying a bow and arrow and climbing through high treetops in the African forest. Only one of these paintings is known to exist today, in the offices of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

The original art was photographed for the magazine by the Colorplate Engraving Company of New York who also did the preparation of color separation plates and all photoengraving work, including the necessary “dot etching” whereby certain details and colors are enhanced and matched to the actual painting. We know who did this work for New Story Magazine because there is a photograph, published in A HALF CENTURY OF COLOR by Louis W. Sipley (Macmillan, 1952), of the rooftop cameras and copy boards where a Wyeth illustration for the February, 1914 issue is being photographed.

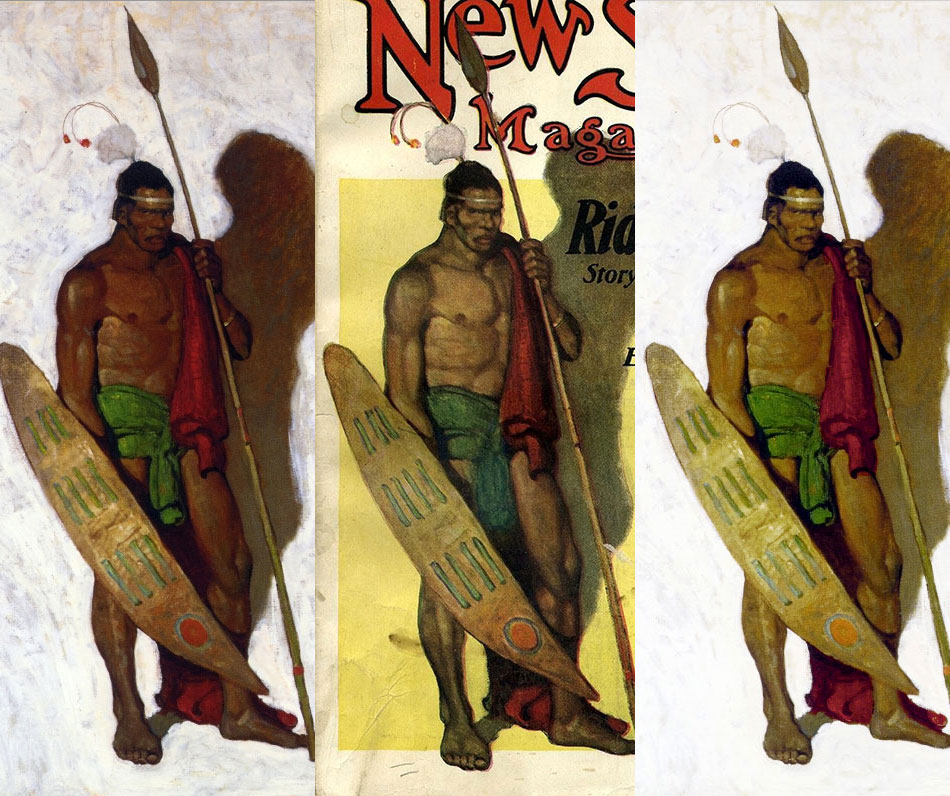

The “African Warrior” illustration above was done to accompany the third installment of H. Rider Haggard's ALLAN AND THE HOLY FLOWER in that issue. Though THE RETURN OF TARZAN is mentioned on the cover, what is found inside is the second part of the serialization of ERB’s THE OUTLAW OF TORN, the second story he had ever written, in late 1911, after A PRINCESS OF MARS and before TARZAN OF THE APES.

Though today we think of art reproduction as being simply a matter of taking a photo and printing it, in 1913 color reproduction required the skills of men who understood the subtleties of getting colored inks to combine on paper through the use of small dots and lines etched into zinc or copper plates and printed on a letterpress. Though photography for color separation was advancing by leaps and bounds, there was always need for the skilled hand in preparing the final printing plates. This process was vital to early 20th century color printing because the photoengraver had a big impact on how the printed illustration looked.

All artwork for the magazine was photographed through a half-tone screen at the actual size it was to be printed, approximately 7 x 10 inches for a pulp magazine cover, on glass plates sensitized with a colloidal film. Four-color printing required that the art be shot four times, once for each process color (yellow, red and blue) and once for the black plate. Different colored filters for each shot would only allow the process color needed to register on the negative. The half-tone screens would also have to be adjusted to different angles to avoid a pattern, or “moire” being formed when the dots were printed next to each other. After all four glass plates were exposed in camera the colloidal film for each was loosened and adhered, or “stripped up,” to sheets of glass to be printed onto copper printing plates and eventually handed over to the color etcher.

The color, or dot, etcher would work with the original art in front of him and make adjustments to dot size on each separate color plate to bring the print's colors and values closer to the original. He had to have a well-honed sense of color and the ability to visualize how the work he did on each plate would affect the other plates and the final print. This work was needed because the dyes used in the photo-separation process were not perfect filters and elements of other colors would come through on each separation and need to be removed or tempered. If a color area was in some way ill-defined or needed adjustment, it was the job of the etcher to make these definitions on the plate. A set of plates could go through as many as four proofs before a final, accurate printing was ready to be made.

The images below show a modern photo of the original art of the African Warrior illustration above (the original measures 42 x 28 inches). The photo is dark and lacking the detail that is in the printed version in the middle. The image on the right shows a color-balanced version, done in Photoshop, bringing the image closer to the magazine cover as printed. Note that there is more use of black or dark brown shadowing to deliniate musculature in the printed version. That is apparently the engraver's enhancement. This is an illustration of how well the photoengraver could capture, and modify, the details and colors of the original painting and what kinds of changes we might expect to find comparing the source painting and the reproduction.

In part 2 we'll examine the Wyeth Tarzan painting as it appeared on its book publications. (Continue)